The Importance of Knowing

It’s useful and powerful to know how something works. The cliché that “knowledge is power” may be a common and overused expression but that does not mean it is inaccurate. Let me illustrate this idea with a story from a different area. I use this rhetorical device often, by the way. I frequently try to illustrate one idea with an analogy from another area. It’s probably a result of being a professor and lecturer for so many years. I try to show the connection between concepts and different examples. It can be helpful and can aid understanding. It can also be an annoying habit.

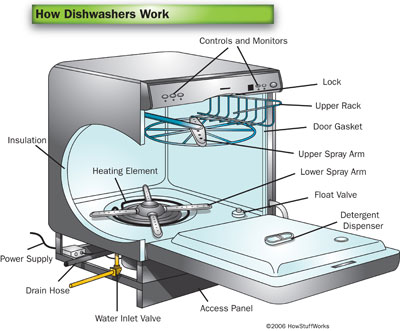

My analogy has to do with a dishwasher appliance. I remember the first time I figured out how to repair the dishwasher in my kitchen. It’s kind of a mystery how the dishwasher even works, because you never see it working (unless you do this). You just load the dishes, add the detergent, close the door, and start the machine. It runs its cycle out of direct view and when the washing cycle is finished, clean dishes emerge. So there’s an input, some internal state where something happens, and an output. We know what happens, but not exactly how it happens. We usually study psychology and cognition in the same way. We can know a lot about what’s going in and what’s coming out. We don’t know as much about what’s going in inside because we can’t directly observe it. But we can make inferences about what’s happening based on the function.

from HowStuffWorks.com

The Dishwasher Metaphor of the Mind

So let’s use this idea for bit. Let’s call it the “dishwasher metaphor“. The dishwasher metaphor for the mind assumes that we can observe the inputs and outputs of psychological processes, but not their internal states. We can make guesses about how the dishwasher achieves its primary function of creating clean dishes based on what we can observe about the input and output. We can also make guesses about the dishwasher’s functions by taking a look at a dishwasher that is not running and examining the parts. We also can make guesses about the dishwasher’s functions by observing what happens when it is not operating properly. And we can even make guesses about the dishwasher’s functions by experimenting with changing the input, changing how we load the dishes for example, and observing how that might affect the outputs. But most of this is careful, systematic guessing. We can’t actually observe the internal behaviour of the dishwasher. It’s mostly hidden from our view, impenetrable. Psychological science turns out to be a lot like trying to figure out how the dishwasher works. For better or worse, science often involves careful, systematic guessing

Fixing the Broken Dishwasher

The dishwasher in my house was a pretty standard early 2000s model by Whirlpool, though sold under the KitchenAid brand. It worked really well for years, but at some point, I started to notice that the dishes weren’t getting as clean as they used to. Not knowing what else to do, I tried to clean it by running it empty. This didn’t help. It seemed like water was not getting to the top rack. And indeed if I opened it up while it was running I could try to get an idea of what was going on. Opening stops the water but you can catch a glimpse of where the water is being sprayed. When I did this, I could observe that there was little or no water being sprayed out of the top sprayer arm. So now I had the beginnings of a theory of what was wrong, and I could begin testing hypotheses about this to determine how to fix it. What’s more, this hypothesis testing also helped to enrich my understanding of how the dishwasher actually worked.

Like any good scientist, I consulted the literature. In this case, YouTube and do-it-yourself websites. According to the literature, several things can affect the ability of the water to circulate. The pump is one of them. The pump helps to fill the unit with water and also to push the water around the unit at high enough velocity to wash the dishes. So if the pump was not operating correctly, the water would not be able to be pushed around and would not clean the dishes. But that’s not easy to service and also, if the pump were malfunctioning, it would not be filling or draining at all. So I reasoned that it must be something else.

There are other mechanisms and operations that could be failing and therefore restricting the water flow within the dishwasher. And the most probable cause was that something was clogging the filter that is supposed to catch particles from entering the pump or drain. It turns out that there’s a small wire screen underneath some of the sprayer arms. And attached to that is a small chopping blade that can chop and macerate food particles to ensure that they don’t clog the screen. But after a while, small particles can still build up around it and stop it from spinning, which stops the blades from chopping, which lets more food particles build up, which eventually restricts the flow of water, which means there’s not enough pressure to force water to the top level, which means there’s not enough water cleaning the dishes on the top, which leads the dishwasher to fail. Which is exactly what I had been observing. I was able to clean and service the chopper blade and screen and even installed a replacement. Knowing how the dishwasher works allowed me to keep a closer eye on that part, cleaning it more often. Knowing how the dishwasher worked gave me some insight into how to get cleaner dishes. Knowledge, in this case, was a powerful thing.

Trying to study what you can’t see

And that’s the point that I’m trying to make with the dishwasher metaphor. We don’t necessarily need to understand how it works to know that it’s doing its job. We don’t need to understand how it works to use it. And it’s not easy to figure it out, since we can’t observe the internal state. But knowing how it works, and reading about how others have figured out how it works, can give you an insight into how the the processes work. And knowing how the processes work can give you and insight into how you might improve the operation, how you can avoid getting dirty dishes.

Levels of Dishwasher Analysis

This is just one example, of course and just a metaphor, but it illustrates how we can study something we can’t quite see. Sometimes knowing how something works can help in the operation and the use of that thing. More importantly, this metaphor can help to explain another theory of how we explain and study something. I am going to use this metaphor in a slightly different way and then we’ll put the metaphor away. Just like we put away the clean dishes. They are there in the cupboard, still retaining the effects of the cleaning process, ready to be brought back out again and used: a memory of the cleaning process.

Three ways to explain things

I think we can agree that there are different ways to clean dishes, different kinds of dishwashers, and different steps that you can take when washing the dishes. For washing dishes, I would argue that we have three different levels that we can use to explain and study things. First there is a basic function of what we want to accomplish, the function of cleaning dishes. This is abstract and does not specify who or how it happens, just that it does. And because it’s a function, we can think about it as almost computational in nature. We don’t even need to have physical dishes to understand this function, just that we are taking some input (the dirty dishes) and specifying an output (clean dishes). Then there is a less abstract level that specifies a process for how to achieve the abstract function. For example, a dishwashing process should first rinses off food, use detergent to remove grease and oils, rinse off the detergent, and then maybe dry the dishes. This is a specific series of steps that will accomplish the computation above. It’s not the only possible aeries of steps, but it’s one that works. And because this is like a recipe, we can call it an algorithm. When you follow these steps, you will obtain the desired results. There is also an even more specific level. We can imagine that there are many ways to build a system to carry out these steps in the algorithm so that they produce the desired computation. My Whirlpool dishwasher is one way to implement these steps. But another model of dishwasher might carry them out in a slightly different way. And the same steps could also be carried out by a completely different system (like on of my kids washing dishes by hand, for example). The function is the same (dirty dishes –> clean dishes) and the steps are the same (rinse, wash, rinse again, dry) but the steps are implemented by different system (one mechanical and the other biological). One simple task but there are three ways to understand and explain it.

David Marr and Levels of Analysis

My dishwasher metaphor is pretty simple and kind of silly. But there are theorists who have discussed more seriously the different ways to know and explain psychology. Our behaviour is one, observable aspect of this picture. Just as the dishwasher makes clean dishes, we behave to make things happen in our world. That’s a function. And just like the dishwasher, there are more that one way to carry out a function, and there are also more one way to build a system to carry out the function. The late and brilliant vision scientist David Marr argued that when trying to understand behaviour, the mind, and the brain, scientists can design explanations and theories at three levels. We refer to these as Marr’s Levels of Analysis (Marr, 1982). Marr worked on understanding vision. And vision is something that, like the dishwasher, can be studied at three different levels.

Marr described the Computational Level as an abstract level of analysis that examines the actual function of the process. We can study what vision does (like enabling navigation, identifying objects, even extracting regularly occurring features from the world) at this level and this might not need to be as concerned with the actual steps or biology of vision. But at Marr’s Algorithmic Level, we look to identify the steps in the process. For example, if we want to study how objects are identified visually, we specify the initial extraction of edges, the way the edges and contours are combined, and the how these visual inputs to the system are related to knowledge. At this level, just as in the dishwasher metaphor, we are looking at species of steps but have not specified how those steps might be implemented. That examination would be done at the Implementation Level where we would study the visual system’s biological workings. And just like with the dishwasher metaphor, the same steps can be implemented by different systems (biological vision vs computer visions, for example). Marr’s theory about how we explain things has been very influential in my thinking and in psychology in general. It gives us a way to know about something and study somethings at different levels of abstraction and this can lead to insights about biology, cognitions, and behaviour.

And so it is with the study of cognitive psychology. Knowing something about how your mind works, how your brain works, and how the brain and mind interact with the environment to generate behaviours can help you make better decisions and solve problems more effectively. Knowing something about how the brain and mind work can help you understand why some things are easy to remember and others are difficult. In short, if you want to understand why people—and you—behave a certain why, you need to understand how they think. And if you want to understand how people think, you need to understand the basic principles of cognitive psychology, cognitive science, and cognitive neuroscience.

Reference

Marr, D. Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information (WH Freeman, San Fransisco, 1982).